I. Introduction: The Giver's Fantasy

There's a fantasy underlying most conventional feedback models: if I say the feedback perfectly, at the right time, in the right way—it will be perfectly received.

No.

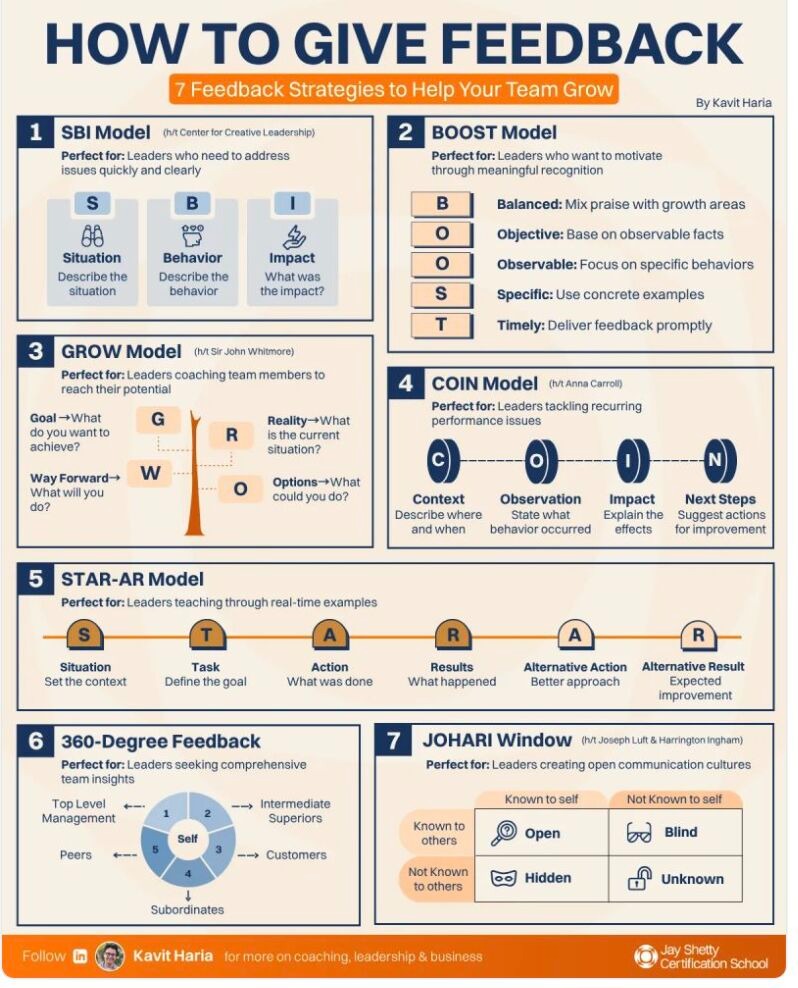

This fantasy drives entire industries of feedback training. Learn the SBI model. Master the BOOST framework. Follow the COIN structure. Get the timing right, choose your words carefully, deliver with proper balance and tone—and the person will hear you, understand you, and change accordingly.

Except they won't. Not always. Not even most of the time.

Because feedback isn't something you do TO someone. It's not a message you deliver, a technique you execute, or a skill you perfect. Feedback happens BETWEEN people—in the living, breathing, unpredictable space of relationship.

When we treat feedback as a one-sided event, we miss what's actually happening. We ignore that the receiver is a complete human being with their own scripts, defenses, contexts, and capacity to hear. We pretend power dynamics don't exist. We act as if timing, emotional state, and environmental stress don't shape what's possible. We forget that meaning emerges from relationships, not from perfect word choice.

Most dangerously, we mistake our models and frameworks for reality itself.

This article offers a different approach—one that honors feedback as a living relational process requiring both giving and receiving, unfolding over time, generating mutual learning. We'll explore a framework that can guide this work, while remembering that the real territory is the relationships we're building together.

But if the giver's fantasy is just that—a fantasy—then what's actually happening in all those feedback models we've been taught? What are they missing?

II. Why Conventional Feedback Models Fall Short

Look at any popular feedback model—SBI, BOOST, COIN, GROW, STAR-AR—and you'll notice something striking: they're all about giving feedback. The entire focus is on what the giver or leader should do, say, and consider.

This reveals a fundamental misunderstanding. These models treat feedback as a transmission problem: if the sender encodes correctly, the receiver will decode accurately. But human communication doesn't work like radio signals. We're creating meaning together in relationships.

Here's what most models leave out:

The receiver's experience. How do people actually hear feedback? What makes them able—or unable—to receive it? What's happening with their nervous system, emotional state, sense of safety?

The relational space. Feedback unfolds within a relationship that has history, power dynamics, trust or distrust, patterns and wounds. That relationship determines what's possible far more than perfect technique.

The ongoing process. These models treat feedback as discrete events. But real feedback is continuous loops of information flowing between people over time.

Context and the whole system. A person who is stressed and overwhelmed can't receive feedback the same way someone who is feeling safe can. Your child is sick. Their dog died. It's winter and they hate winter. The company announced layoffs. Traffic was terrible. All these threads weave through the conversation. There's no simple cause and effect.

The hidden assumption: If I do my part correctly, the feedback will work. This puts all the responsibility—and an illusion of control—on the giver. It guarantees disappointment when even "perfect" feedback doesn't land as intended.

These conventional models aren't useless—they're helpful tools. But here's the problem: we've been mistaking the map for the territory. And that confusion is costing us the quality of our relationships.

III. The Map Is Not the Territory

Alfred Korzybski¹ gave us one of the most important insights about human understanding: "The map is not the territory."

A map of New York City shows streets, landmarks, subway lines. It helps you navigate. But you can't smell the bagels or feel the subway rumble by looking at a map. The map leaves out infinitely more than it includes.

Feedback models work the same way. SBI, BOOST, COIN—they give us language and structure. But they're representations, not reality.

But the territory? That's the actual lived experience. The flutter in your chest approaching a difficult conversation. The way their jaw tightens when you mention the project. The unspoken history between you. The power dynamics that trigger a desire to please. The way your nervous systems co-regulate or dysregulate. What gets triggered, what defenses arise, what possibilities emerge or collapse in real time.

The territory is reality–messy, complex, alive, full of nuance that no map can capture.

We need maps for orientation, patterns, vocabulary. But maps become dangerous when we mistake them for territory itself—when we think following the model means we're handling reality.

The deeper work happens in relational space—the territory where two unique human beings meet, each bringing their full complexity. This requires all our intelligences: emotional intelligence reading shifts in tone, somatic intelligence feeling tension or relaxation, relational intelligence sensing what's possible now, intuition picking up what's not being said.

The framework we'll explore is also a map, but of a different flavor. Use it as a guide. But never forget: the real work happens in the territory—in the living relationship you're creating together, one imperfect conversation at a time.

So if the territory is reality itself—the actual living, breathing, messy relational space—how do we understand what's really happening there? What does feedback look like when we see it as it actually is?

IV. Feedback as Characteristic of Living Systems

Humans are living systems. We're not machines that can be programmed with inputs to produce predictable outputs. We're complex, organic beings in continuous relationship with our environment and each other.

Ongoing feedback is fundamental to how living systems function. As Donald MacKay² stated, "Information is a distinction that makes a difference"—later echoed by Gregory Bateson³ as "a difference which makes a difference."

That insight reframes how we can approach feedback.

Feedback isn't something you do TO someone, or even WITH someone occasionally. It is what is always happening between people in living relationships. Information flows constantly—in words, body language, what gets done or left undone, in the energy between you. The question isn't whether feedback is happening. It's whether you're paying attention to it and using it to learn.

How we think about learning matters. In living systems, feedback flows in multiple directions simultaneously, generating learning at many levels, conscious and unconscious.

The dynamics of learning are why conventional models that focus only on "giving" feedback miss the point. Tending to receiving is as important as tending to giving. If someone can't receive—because they're stressed, defensive, unclear about safety, or simply not ready—then no amount of perfect delivery will create learning.

Here are three core principles about feedback in living systems:

1. Feedback flows in circular loops, not linear lines. You share an observation. They interpret it through their filters. Their interpretation triggers a response in you. Your response affects their next move. Round and round. There's no clear beginning or end, no simple cause and effect. This is how living systems work.

2. Context shapes everything, and everything is connected. Feedback is a part of a whole; it’s not an event on its own. The same words mean different things in different contexts. Feedback given in crisis feels different than feedback in calm reflection. Feedback from a supervisor carries different weight than feedback from a peer. And none of this happens in isolation. Many threads move through every conversation.

3. Defense mechanisms are normal information. When feedback touches something tender, defenses arise: deny, ignore, distort, avoid, attack, justify. These aren't character flaws. They're protective mechanisms serving important purposes. They tell you something important has been activated. Learning to work with defenses rather than against them is essential.

When feedback is working well, it generates learning (though not always the same learning for everyone), clarity about next steps, balance and equilibrium, flow of energy and information, signal emerging from noise.

Feedback is not an event you schedule and complete. It's an ongoing process, a continuous feedback loop that—when tended well—can become the basis of mutual learning and trust.

Understanding ourselves as living systems shifts how we can approach feedback. Now let's explore a framework that can guide this work—one that honors the giver's fantasy for what it is, while opening up what's actually possible in the territory...

VI. The Framework: A Map for the Territory

Now we come to a different map—a framework that can guide your navigation of the whole feedback territory. Remember: this is a map, not the territory itself. Use it for orientation. Hold it lightly. Stay present to the living reality unfolding between you and another person.

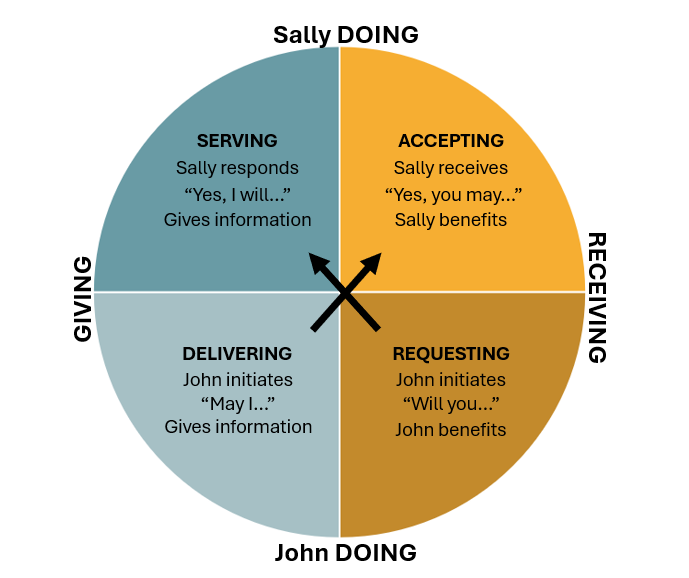

This framework illuminates the often-invisible dynamics of who initiates giving feedback, who receives, and who benefits—distinctions that are essential for understanding what's actually happening in any exchange between people. It involves consent from both sides after an understanding of language and possibilities is established.

An Introduction to the Feedback Exchange Framework

Every feedback interaction can be understood through two distinct dynamic exchanges, based on two questions:

Who initiates?

Who will benefit?

These two questions create two types of exchanges, each with two sides. Understanding which exchange you're in—and which side of that exchange—helps clarify expectations, honor different needs, create consent, and build reciprocity in relationships.

Now, let's explore how these exchanges work, using John and Sally as our two people in a feedback relationship.

Feedback Exchange Framework

Exchange Type 1: DELIVERING/ACCEPTING (Asking to Give)

How you might typically think about giving feedback, keeping receiving in mind.

John asks Sally if he can give her feedback for her benefit. Sally decides whether to accept. If yes, John delivers what he wants Sally to know, in a way she can hear it.

- John initiates: "May I share feedback with you?"

- Sally considers and responds (yes, no, or "yes, but not now/in a different way")

- When yes, John delivers the feedback

- Sally accepts what John shares

- The benefit is for Sally's learning/development

Exchange Type 2: REQUESTING/SERVING (Requesting to Receive)

John asks Sally to give him feedback for his benefit. Sally decides whether to serve his request. If yes, Sally provides what John asked for, in a way he wants.

- John initiates: "Will you give me feedback?"

- Sally considers and responds (yes or no)

- When yes, Sally provides the information John requested, in the way he wants it

- John accepts what Sally gives him

- The benefit is for John's learning/development

Why These Distinctions Matter

Understanding which exchange you're in helps you:

Clarify expectations. When you know who initiated and will benefit, and what kind of exchange is happening, you can be clear about what you're asking for and what you're offering.

Honor different needs. Sometimes you need to ask to give feedback for another's benefit (DELIVER). Sometimes you need to request to receive feedback for your benefit (REQUEST). Sometimes you need to be willing to accept feedback someone wants to give you (ACCEPT). Sometimes you need to give the feedback others request from you (SERVE). All are valid.

Create consent. Feedback requires permission. People need to be capable of receiving information when it's given, which means they have the right to set boundaries about when and how feedback happens. As relationships develop, explicit asking can become implicit understanding—and consent remains essential.

Build reciprocity. Healthy feedback relationships move through both types of exchanges over time. All aspects of reciprocal relationships require active participation.

Examples

Example: DELIVERING/ACCEPTING Exchange

John (supervisor) notices Sally has been struggling with client presentations. He wants to help her improve.

DELIVERING (John's side): John approaches Sally. "May I share some observations about yesterday's client presentation? I think this could help you land these more effectively."

ACCEPTING (Sally's side): Sally pauses. She's feeling a bit defensive, but she knows John cares about her development and she trusts him. "Yes, but honestly I'm pretty stressed right now. Can we do this after lunch when I have more headspace?"

John agrees and they meet after lunch. He shares specific observations: "In yesterday's presentation, when the client asked about the timeline, you said 'I think we can probably do that.' The word 'probably' undermined your authority. What I've seen work better is stating what you know confidently, then being direct about what needs to be determined: 'We can deliver X by this date. Let me confirm Y with the team and get back to you tomorrow.'"

Sally accepts the feedback, asks clarifying questions about other moments in the presentation, and they discuss what she'll practice before her next client meeting.

This exchange honors both people: John gets to share what he wants Sally to know for her benefit. Sally gets to set boundaries about when and how she receives it, ensuring she can actually take it in.

Example: REQUESTING/SERVING Exchange

John wants to get better at client presentations and knows he needs an external perspective.

REQUESTING (John's side): John approaches Sally. "Will you give me feedback on my presentation style? I want to know what's working and what's not. Can you be really direct with me? I can handle it and I need the truth more than I need to feel comfortable."

SERVING (Sally's side): Sally considers whether she can serve this well right now. "Yes, I can do that. Let me sit in on your Thursday presentation with the Anderson team, and we'll debrief right after while it's fresh."

After Thursday's presentation, Sally provides the specific, direct feedback John requested: "You started strong with the data, but when they pushed back on pricing, you got tentative. Your voice went up at the end of sentences like you were asking permission. When you're questioned, that's actually when you need to sound most confident—even if you're saying 'I don't know, let me find out.'"

John accepts the feedback, explores it with Sally ("Was it just pricing or other topics too?"), and identifies what he wants to practice before his next presentation.

This exchange honors both people: John gets the help he asked for, in the direct way he specified. Sally gets to contribute by serving John's request—but only after confirming she can provide what he's asking for.

The Key Difference

DELIVERING/ACCEPTING: John initiates because he has something he wants Sally to know for her benefit.

REQUESTING/SERVING: John initiates because he wants something from Sally for his benefit.

Both exchanges require consent. Both can happen in the same relationship. Healthy feedback relationships move fluidly between both types of exchanges.

What the Feedback Exchange Framework Offers

This map gives you:

- Language for the different dynamics of feedback that are often invisible

- Clarity about whose needs are being served

- Permission to move through different exchanges as needs shift

- Orientation when you're lost in the territory

What it doesn't give you:

- A script for what to say

- Guarantee that it will work

- Control over the other person's reactions

- A way to avoid messiness and discomfort

Use this framework as a guide. But remember: the real work happens in a relationship, in the territory where two unique human beings meet and attempt to create something together.

The framework provides the map. But to navigate the territory well, you need to bring something essential: your grounded, authentic presence. This is where True Self leadership comes in...

VII. True Self Leadership: What You Bring to the Framework

Your own state matters more than your technique. Most conventional feedback models don't address this fact (though approaches like the IAMX Define Your True Self⁴ course and Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication⁵ do).

Before you can create space for a feedback process, you need to be aware of your own nervous system, recognize your own reactivity, and connect to your authentic presence. This is True Self leadership—the foundation you bring to any feedback exchange, regardless of which exchange you're in.

The process is leading from your Best Self, learning from your Drama. Not one or the other. Both have essential roles.

Best Self: Your Responsive Nervous System States

Your Best Self is you when you're in a responsive nervous system state, connected to what matters most. This state is central to transformational leadership. It's characterized by:

- Broader perspective beyond the immediate exchange

- Connection to values and purpose—why this relationship matters

- Capacity for curiosity rather than defensiveness

- Relational awareness of what's happening between you

- Strategic clarity about what truly matters

When you're in Best Self, feedback becomes an act of care rather than correction. You can hold complexity. You can allow the conversation to unfold rather than controlling it toward a predetermined outcome. The conversation is based on an existing connection with another.

Drama: Your Reactive Nervous System States

Drama is what emerges when you're triggered, defensive, contracted—patterns that often fuel team dysfunction. It includes:

- Defense mechanisms: deny, ignore, distort, avoid, attack, justify

- Scripts that make it hard to hear feedback accurately

- Reactions that arise before you can choose

Drama isn't bad. It's information about what matters to you.

When Drama arises, it's telling you something important. Maybe this topic touches a wound. Maybe you're not feeling safe. Maybe your needs aren't being met. This is where you'll find your unmet needs.

The issue isn't having Drama. The issue is being unconscious of it, letting it run the show.

Learning from Drama

True Self leadership means developing the capacity to orient from your Best Self and learn from Drama.

You're rarely completely in one state or the other. Responsive and reactive states are usually a complex combination. The practice is about noticing where you're primarily orienting from and being aware of what's happening within yourself.

When you're in Drama: Notice it. Welcome it as information. Get curious about what's going on. Give yourself what you need.

When you're in Best Self: Appreciate it. Use it—this is when learning from Drama becomes possible. Know it won't last forever.

The movement between responsive and reactive states is natural. Building capacity means getting more fluid at recognizing where you are and choosing how to respond, rather than being unconsciously driven by reactivity.

The 100% Rule: Developing the Capacity to Choose

In IAMX, we work with the 100% Rule: you are 100% responsible for your experience, as you can be.

This doesn't mean everything is your fault or that you get to control everything. It means when you're in a responsive state, you can develop the capacity to choose your responses to situations. When you're reactive, this capacity isn't available. That's important to recognize.

In feedback contexts:

- I'm responsible for my state and what I’m bringing

- I'm responsible for asking for what I want or need

- I'm responsible for my contribution to this relationship

This isn't about controlling outcomes. It's about showing up authentically while honoring the other person's full agency. Knowing that responsibility, the ability to “respond,” is a continuum that you develop over time. There will be times when you can’t take responsibility, and that’s just human.

Why This Matters for the Framework

You cannot navigate the framework well if you've been hijacked by your nervous system. Whether you're in a DELIVERING/ACCEPTING exchange or an REQUESTING/SERVING exchange—your state determines what's possible.

When you're in Drama (reactive states):

- You can't truly ACCEPT someone's offer to deliver feedback—you're too defended to receive

- You can't genuinely SERVE someone's request—you're too contracted to give freely

- You can't authentically DELIVER (ask to give)—you might demand rather than request

- You can't clearly REQUEST (ask to receive)—you might be too angry or ashamed to ask for help

When you're in Best Self (responsive states):

- You can ACCEPT with genuine openness, even if what's shared is difficult

- You can SERVE from care rather than obligation

- You can DELIVER (ask to give) from clarity about what you want them to know

- You can REQUEST (ask to receive) from curiosity rather than fear

The framework shows you the territory of feedback exchanges. True Self leadership is how you can successfully navigate that territory.

A Simple Self-Check Practice

Before engaging in any feedback exchange, ask yourself:

- What state am I in right now? (Best Self? Drama? Some of both?)

- Which exchange am I initiating or responding to? (Am I asking to give feedback? Being asked to accept someone's offer to give feedback? Requesting feedback? Being asked to serve someone's request for feedback?)

- What do I genuinely want or need from this exchange?

- Am I able to be present with another person's experience, or am I too caught in my own?

If you're too caught in Drama to be present, that's okay. It means this isn't the right time. Do your own work first—process with a colleague or coach, journal, take a walk, reconnect to what personally matters. Then come back to the conversation when you have more capacity.

Conclusion: Beginning the Journey

We've explored why the giver's fantasy falls short, why we need to distinguish the map from the territory, and what it means to see feedback as characteristic of living systems. We've introduced a framework that illuminates the invisible dynamics of feedback exchanges—the DELIVERING/ACCEPTING exchange (asking to give) and the REQUESTING/SERVING exchange (asking to receive).

But a map is just a beginning.

The real work happens in the messy territory of actual relationships—where power dynamics complicate everything, where defense mechanisms arise unbidden, where reactive environments make learning nearly impossible.

In Part 2, we venture into that territory together. We explore the specific challenges you'll encounter and practical moves for navigating them. We examine what makes feedback life-affirming rather than soul-crushing.

For now, begin here:

- Notice which exchange most of your feedback interactions fall into

- Practice connecting to your Best Self before initiating either exchange

- Get curious about your Drama when it arises

- Hold the framework lightly as you pay attention to what's actually happening

The territory of feedback is where some of the most important personal and organizational work happens—the work of building relationships that can handle truth, creating cultures where people can be authentic, and tending the aliveness that makes everything else possible.

Welcome to the journey!

Footnotes

¹ Alfred Korzybski (1879-1950) was a Polish-American philosopher who developed general semantics and coined the famous phrase "the map is not the territory" in his 1933 work Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. Learn more: Wikipedia - Alfred Korzybski

² Donald MacKay (1922-1987) was a British physicist and professor at Keele University known for his contributions to information theory and the theory of brain organization. His work explored the relationship between information, mechanism, and meaning. Learn more: Wikipedia - Donald MacCrimmon MacKay

³ Gregory Bateson (1904-1980) was an English anthropologist, social scientist, and cyberneticist who described information as "a difference which makes a difference" in his influential 1972 work Steps to an Ecology of Mind. His work profoundly influenced systems thinking and family therapy. Learn more: Wikiquote - Gregory Bateson

⁴ IAMX Define Your True Self Course is a transformational leadership program that helps leaders access their authentic presence and orient from their responsive self rather than reactive patterns. The course integrates nervous system awareness, emotional intelligence, and strategic clarity. Learn more: IAMX Define Your True Self

⁵ Marshall Rosenberg (1934-2015) was an American psychologist who developed Nonviolent Communication (NVC), a communication process that emphasizes compassion, empathy, and honest self-expression. His work has influenced conflict resolution and interpersonal communication worldwide. Learn more: Center for Nonviolent Communication