I. You Have the Map—Now What?

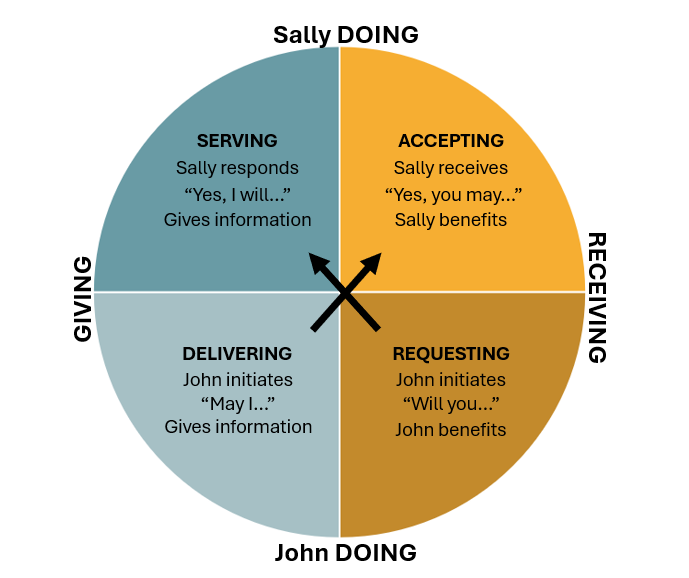

In Part 1: A Living Process of Feedback, you learned the framework: DELIVERING/ACCEPTING and REQUESTING/SERVING exchanges. You understand that feedback requires both giving and receiving, that it unfolds over time, that it's a living relational process.

But the territory is tricky.

Why? Because even with a good map, we're still treating feedback as truth about the receiver instead of information about the giver's experience.

When you DELIVER feedback, you're not revealing truth about them—you're revealing YOUR experience, YOUR perspective, YOUR needs.

When you REQUEST feedback, you're asking someone to share THEIR experience, THEIR perspective—not the truth about you.

This removes the minefield of judgment and blame. It activates the 100% Rule. It creates space for mutual learning.

Let's revisit the framework from Part 1:

Feedback Exchange Framework

Now let's explore how to work in the territory where power dynamics complicate everything, where defense mechanisms unconsciously arise, where people have been directly hurt by each other's actions.

II. Two Types of Feedback (Both Filtered Through the Giver)

Before we explore the territory, we need to distinguish two types of feedback situations:

Type 1: Personal Impact Feedback

"When you did X, I experienced Y. Here's the impact on ME."

This is interpersonal feedback where you're sharing how someone's behavior affected you personally.

Examples:

- "When you interrupt me in meetings, I feel dismissed and I shut down"

- "When you committed to something and didn't follow through, I felt let down and it eroded my trust"

- "I felt attacked by the tone of your email"

About the giver's experience: This is 100% about sharing how someone's behavior affected you. You're not claiming an absolute truth about them—you're owning your experience of their impact. Notice the use of "I" statements here; it’s a good practice!

Type 2: Organizational/Role Feedback

"The work/project/role requires X, and currently you're doing Y."

This is feedback about meeting organizational needs, role expectations, or professional standards.

Examples:

- "Client presentations need to be finalized 24 hours before meetings. Currently they're being finished 2 hours before, which is creating unnecessary stress for the team"

- "When you hit a technical roadblock, the team needs you to flag it within a day so we can problem-solve together. The last two times you got stuck, work stalled for a week before anyone knew there was an issue"

- "When project scope changes, the team needs that information immediately so we can adjust our work. Our recent pivot wasn't communicated until a week later, which created confusion and duplicate work"

About organizational interpretation: Even organizational feedback is filtered through YOUR interpretation of what the work needs. Another leader might interpret the same situation differently. So while this isn't about personal impact on you, it's still about YOUR perspective on organizational needs—not singular truth.

Why Both Types Still Require the Same Stance

- Not making the receiver wrong or bad

- Owning your perspective (not claiming absolute truth)

- Staying curious about their experience

- Remaining open to mutual learning

- Holding the 100% Rule: you're 100% responsible for your experience and interpretation

III. Reclaiming Your Experience (The 100% Rule in Action)

When you understand that feedback reveals YOUR experience rather than singular truth about them, the framework comes alive differently:

When you DELIVER (ask to give): You're sharing YOUR experience of their impact on you (Type 1) OR your interpretation of what the work/role needs (Type 2)—NOT delivering truth about who they are.

When you ACCEPT (receive someone's offer to give): You're receiving THEIR experience of your impact OR their interpretation of what the work needs—NOT receiving truth about who you are.

When you REQUEST (ask to receive): You're asking for THEIR experience of your impact—NOT asking for the truth about you.

When you SERVE (provide what's requested): You're offering YOUR experience/perspective—NOT delivering the truth about them.

There's no singular truth to defend against or fight over. There's only different experiences to explore and learn from.

IV. What You Bring to the Territory: Best Self and Drama

Before we explore the specific challenges in the territory, you need to understand what you're bringing to every feedback conversation: your nervous system state.

From Part 1, you learned about Best Self and Drama—two different nervous system states that shape what's possible in feedback.

Best Self is your responsive nervous system state. When you're in Best Self, you're:

- Calm and connected to what matters most

- Able to stay curious rather than defensive

- Aware of what's happening between you and the other person

- Capable of holding complexity and uncertainty

Individual Best Sparks Team Best

Drama is your reactive nervous system state. When you're in Drama, you're:

- Triggered, defensive, or contracted

- Operating from protection rather than connection

- Unable to access curiosity or perspective

- Driven by automatic reactions rather than conscious choice

Drama Happens by Default

Drama isn't bad. It's information about what matters to you and what's been activated. The issue isn't having Drama—it's being unconscious of it and letting it run the conversation.

You're rarely completely in one state or the other. Most of the time, you're some combination of both. The practice is noticing which state you're primarily in and choosing how to respond.

Why this matters for the territory:

When you're in Drama, you can't truly receive someone's experience without hearing it as truth about you. You can't share your experience without making them wrong. You can't stay curious about their perspective.

When you're in Best Self, you can hold "this is their experience" even when it's difficult to hear. You can own your experience without attacking their character. You can stay open to learning.

The challenges we're about to explore—power dynamics, defense mechanisms, interpersonal harm—all become more navigable when you can recognize your state and do your own work before (or during) the conversation.

V. Challenge 1: Power Dynamics

Power dynamics complicate feedback because power makes one person's experience feel like truth. It’s important to be clear, not ambivalent, about power.

The Core Challenge

When feedback comes from someone with power over you—someone who affects your opportunities, salary, or standing—their experience can feel like a verdict rather than just their perspective.

Even in flat organizations, hierarchy affects reception. The CEO's "interpretation" lands differently than a peer's observation.

How This Reframe Helps

For those with power:

- Name that you're sharing YOUR experience/interpretation, not truth: "Here's what I'm seeing... I could be missing something"

- Explicitly invite their perspective: "Help me understand your experience of this situation"

- Acknowledge the power dynamic: "I know my role creates weight here. I want you to feel as safe as possible being honest"

For those with less positional power (while remembering you still have personal power):

- Remember: this is THEIR experience, not truth about you

- You can receive their experience without it defining you

- You can share YOUR experience back (when safe to do so)

- The 100% Rule still applies: you're responsible for your response

- Your personal power includes: your voice, your boundaries, your choices about how you engage

Examples

Type 1 (Personal Impact) with Power

Upward (individual contributor to leader):

Maya, an individual contributor (IC), approaches her VP, Sarah. "Sarah, can I share something? When you changed the project direction in yesterday's meeting without discussing it with the team first, I felt blindsided. I lost confidence that my input matters. I know you're the VP and have the authority to make those calls—I'm just sharing how it landed for me."

Sarah pauses. She didn't realize the impact. "Thank you for telling me. I was reacting to what the client said in our morning call. I should have looped you in first. Help me understand—what would have made that transition smoother for you?"

They explore together. Maya learns about the client pressure. Sarah learns about the team's need for context. They problem-solve how to handle future direction changes.

Downward (leader to IC):

Tom, a team lead, approaches his direct report Jordan. "Jordan, may I share an observation? When you pushed back aggressively on my suggestion in yesterday's team meeting, I felt undermined in front of the team. I'm curious about your experience—what was happening for you?"

Jordan tenses initially, then relaxes. "I didn't realize it came across that way. I was frustrated because I'd tried that approach last month and it failed. I should have shared that context differently."

They discuss how Jordan can raise concerns without Tom feeling undermined, and how Tom can make space for dissent without it feeling like an attack.

Type 2 (Organizational) with Power

Downward (leader to IC):

Sarah, the VP, approaches Maya. "Maya, I need to talk about the client report deadlines. Our standard is 24 hours before client meetings, and the last three reports came in 2 hours before. That doesn't give the team time to review. Help me understand what's happening on your end—is there something about the process that's not working?"

Maya explains that she's waiting for data from another department that consistently arrives late. Sarah realizes this is a systems problem, not a Maya problem. They brainstorm solutions together.

Practical Moves

- Create space to opt out: "Is this a good time, or do you need to pause?"

- Check in about their experience: "How are you taking this in?"

- Be especially mindful when you have power: your interpretation carries more weight

- Build relational trust over time through repeated positive experiences

V. Challenge 2: Defense Mechanisms

Defense mechanisms arise when we hear feedback as truth about us rather than the giver's experience.

The Core Challenge

When feedback touches something tender, defenses arise automatically: deny, ignore, distort, avoid, attack, justify. This is your nervous system protecting you—not weakness or resistance.

How This Reframe Helps

When you can hear "This is how it landed for them" instead of "This is what's wrong with me," defenses often soften.

Their experience doesn't define you. It's data. Information. A difference that could make a difference.

Working With Your Own Defenses

When receiving feedback:

- Notice the defense arising (you’re human, it will happen!)

- Pause and breathe (take as long as you need)

- Remind yourself: "This is their experience, not truth about me"

- Get curious: "What might I learn from their perspective?"

- Ask clarifying questions instead of defending

When giving feedback and encountering defenses:

- Remember: their defense is information about what got activated

- Don't push through defenses—work with them

- Reaffirm: "I'm sharing my experience, not making you wrong"

- Invite their perspective: "What's your experience of this situation?"

Examples

Type 1 (Personal Impact) with Defenses

The situation: John approaches his colleague Lisa. "Lisa, when you interrupted me three times in yesterday's meeting, I felt dismissed and I shut down. I stopped contributing."

Lisa's defense activates (justify): "I wasn't interrupting—I was trying to add important information before we moved on!"

John works with the defense rather than against it: "I hear that you were trying to contribute. And I'm sharing that from my experience, it felt like interruption and it shut me down. Can we talk about how we can both contribute without that happening?"

Lisa softens. "I didn't realize it affected you that way. Maybe I can write my points down and share them when you've finished?"

They find a solution together.

Type 2 (Organizational) with Defenses

The situation: Manager Chris approaches team member Alex. "Alex, the project deadline is Friday and we're tracking two days behind. I need to understand what's happening so we can problem-solve together."

Alex's defense activates (blame): "I'm behind because marketing didn't get me the brief until last week!"

Chris works with the defense: "I hear that the late brief created challenges. Let's talk about what you need from me to hit Friday's deadline, or if we need to adjust the timeline."

Alex relaxes. They discuss options together rather than fighting about whose fault it is.

Practical Moves

- Welcome defenses as information, not obstacles

- Don't make defenses wrong (like saying, “Don't be defensive!")

- Slow down when defenses arise

- Reaffirm you're sharing experience, not truth

- Return to curiosity

Learn to Soften Defenses

VI. Challenge 3: Interpersonal Impact Feedback (When You've Been Directly Harmed)

This is the hardest territory: when someone's behavior directly harmed you and you need to address it.

The Core Challenge

When you've been hurt, disappointed, let down, or harmed by someone's actions, there's emotional charge. Your nervous system is activated. It's hard to stay in "this is my experience" rather than "you are wrong/bad."

How This Reframe Helps

The shift from "You are X" to "When you did X, I experienced Y" changes the conversation:

"You are X" (making them wrong):

- "You're unreliable"

- "You're disrespectful"

- "You don't care"

"When you did X, I experienced Y" (owning your experience):

- "When you didn't show up for the meeting we scheduled, I felt disrespected and it eroded my trust"

- "When you committed to delivering that report and didn't follow through, I felt let down and it created problems for my timeline"

- "When you spoke over me in the client meeting, I felt dismissed and undermined"

This removes the character attack while honoring the real impact.

Examples Across Hierarchy

Peer to Peer

Alex and Jordan are colleagues on the same team. Last week, Jordan committed to reviewing Alex's presentation draft but never did it.

Alex initiates: "Jordan, can we talk? Last week when you committed to reviewing my presentation draft and then didn't do it, I felt let down. I had to present without feedback and I could have really used your input. I need to understand—can I count on you when you commit to something, or do I need to plan differently?"

Jordan pauses. "You're right. I dropped the ball. I got pulled into a client emergency and it completely slipped my mind. I should have reached out to tell you I couldn't do it. I'm sorry."

Alex: "I appreciate that. What would help you remember next time, or let me know if you can't follow through?"

They problem-solve together about communication when commitments can't be met.

IC to Leader (Upward)

Sam is an individual contributor. His manager Taylor changed the project scope in a meeting without discussing it with Sam first—after Sam had spent two weeks on the original plan.

Sam initiates: "Taylor, I need to share something difficult. When you changed the project scope in yesterday's meeting without discussing it with me first—after I'd spent two weeks on the original plan—I felt blindsided and like my work didn't matter. I know you have the authority to make those calls. I'm just sharing how it landed for me and asking if there's a way we can communicate about scope changes earlier."

Taylor: "I didn't realize the impact. You're right—I should have talked with you first. I got new information from the client and reacted without thinking about how it would land with the team. Going forward, can we schedule a quick sync before I make scope changes?"

They establish a new communication pattern together.

Leader to IC (Downward)

Taylor is a manager. Her direct report Sam publicly disagreed with her strategy in front of a client, creating confusion.

Taylor initiates: "Sam, we need to talk about what happened in the client meeting. When you publicly disagreed with the strategy I'd presented, in front of the client, I felt undermined. It created confusion for the client and made it harder for me to lead the conversation. I'm curious about your experience—what was happening for you that made you speak up at that moment?"

Sam: "I was concerned the strategy wouldn't work based on what I knew about their systems. But you're right—I should have flagged that with you privately, not in the meeting."

Taylor: "I appreciate you wanting to protect us from going down the wrong path. Let's figure out how you can raise concerns in the moment without it undermining my ability to lead the conversation."

They problem-solve together about how Sam can contribute his expertise while respecting Taylor's role.

Practical Moves

For the person giving feedback (the one who was harmed):

- Check your state first: Are you in Drama or Best Self?

- If Drama, do your work first before the conversation

- Own your experience without making the other person bad/wrong

- Be specific about the behavior and the impact

- Stay curious about their perspective

- Be clear about what you need going forward

For the person receiving feedback (being told you caused harm):

- Breathe and notice your defenses

- Remember: this is their experience, not truth about your character

- You can hear their pain without it defining you

- Get curious: "Tell me more about how that landed for you"

- Acknowledge impact even if intent was different: "I hear that it hurt you, even though that wasn't my intention"

- Problem-solve together: "What do you need from me going forward?"

VII. What Makes Feedback Life-Affirming

Feedback becomes life-affirming when:

1. Both People Can Own Their Experience Without Making the Other Wrong

"This is my experience" + "This is your experience" = mutual learning.

No fighting over who's right. No character attacks or judgments or blame. Just different perspectives creating new understanding.

Two colleagues have different experiences of the same meeting. One felt energized by the debate; the other felt attacked. Neither is wrong. Both perspectives are valid. Together, they create a fuller picture of what happened and how to approach future conversations.

2. Feedback Becomes Exploration Rather Than Correction

Curiosity replaces certainty. Questions replace pronouncements. Learning replaces fixing.

"Help me understand your experience" becomes the default as you’re ready to explore.

A manager notices an employee's presentation style differs from what she expected. Instead of correcting it ("You need to do it this way"), she gets curious: "I noticed you took a different approach than I suggested. Help me understand your thinking—what were you optimizing for?" She learns the employee was adapting to what he'd observed about the client's preferences. His adaptation was strategic, not a mistake.

3. The Territory Becomes Safe Enough for Honesty

Over time, groups of people can learn to share difficult experiences without feeling attacked. Trust builds through repeated experiences of being heard. Defenses soften because feedback isn't treated as truth about character. Both people get to be fully human—Best Self AND Drama.

A team that's been working together for two years has built enough safety that they can say things like:

- "That comment triggered something in me. Give me a minute."

- "I don't think I'm in the right state for this conversation right now. Can we talk tomorrow?"

- "I'm noticing I'm getting defensive. That probably means you're touching something important."

The safety allows honesty about their internal states, which paradoxically makes the feedback conversations easier.

4. Reciprocity Exists

Both people initiate both types of exchanges over time. Both people share impact and receive impact. Both people make requests and serve requests. Power doesn't prevent upward feedback.

In healthy feedback relationships, you see patterns like:

- The manager requests feedback about their leadership style

- The IC offers observations about team dynamics

- The manager shares impact when the IC misses deadlines

- The IC shares impact when the manager's communication creates confusion

- Both people move fluidly through all four quadrants of the Feedback Exchange Framework

VIII. Concrete Practices for Working in the Territory

Before Any Feedback Conversation

1. Check your state:

- Am I in Best Self or Drama?

- Best Self is your responsive nervous system state—when you're calm, connected to what matters, and able to stay curious

- Drama is your reactive nervous system state—when you're triggered, defensive, or contracted

- If Drama, what do I need to do - so I can learn from my drama?

2. Clarify what type of feedback this is:

- Is this about personal impact on me? (Type 1)

- Is this about organizational/role needs? (Type 2)

- Either way: Am I clear I'm sharing MY experience/perspective, not absolute truth?

3. Check your intention:

- Am I trying to make them wrong, or understand their experience?

- Am I trying to fix them, or problem-solve together?

- Am I protecting being right, or creating connection?

During the Conversation

1. Name the exchange explicitly:

- "May I share my experience of yesterday's meeting?" (DELIVERING)

- "Will you help me understand how I came across in the presentation?" (REQUESTING)

2. Own your experience/perspective:

- "When you did X, I experienced Y" (Type 1)

- "My perspective is that the work needs X" (Type 2)

- "This is my experience—I could be missing something"

3. Invite their experience:

- "What was happening for you?"

- "How did that land for you?"

- "Help me understand your perspective"

4. Work with defenses (yours and theirs):

- Notice when they arise

- Don't make them wrong

- Reaffirm you're sharing experience, not singular truth

- Return to curiosity

5. Stay connected to the relationship:

- This conversation is part of an ongoing relationship

- You're building something together, not fixing each other

- Hard conversations strengthen connection and build trust

After the Conversation

1. Reflect:

- What did I learn about their experience?

- What did I learn about my experience?

- What's different now?

2. Follow through:

- If you agreed to change something, do it

- If you asked for something, notice if you receive it

- Check in over time: "How's this working?"

3. Build the pattern:

- Each conversation makes the next one easier

- Trust builds through repeated positive experiences

- The territory becomes more familiar

IX. Living in the Territory

You now have both the map (the framework from Part 1) and a way to work in the territory (feedback reveals the giver's experience).

The map shows you what's possible: DELIVERING/ACCEPTING and REQUESTING/SERVING exchanges where both people are honored.

The territory shows you what's real: power dynamics, defense mechanisms, relational wounds, emotional charge.

The practice is this:

Hold the map lightly. Stay present in the territory. Remember feedback is about the giver's experience. Own your 100% responsibility. Stay curious about their experience. Build relationships that can handle honesty. Trust that learning happens in the messy middle.

The work of feedback is the work of building relationships where people can be fully human—reactive and responsive, defended and open, struggling and growing.

This is how you create cultures where feedback becomes mutual learning instead of soul-crushing correction.

This is how you tend to the aliveness of connection that makes everything else possible.